category_news

High uncertainty in climate impact of global forests; a call for more complete estimation

The summer of 2023 leaves an image of burning forests globally. However, this is not the total picture. What the real role of global forests in climate change is, remains highly uncertain.

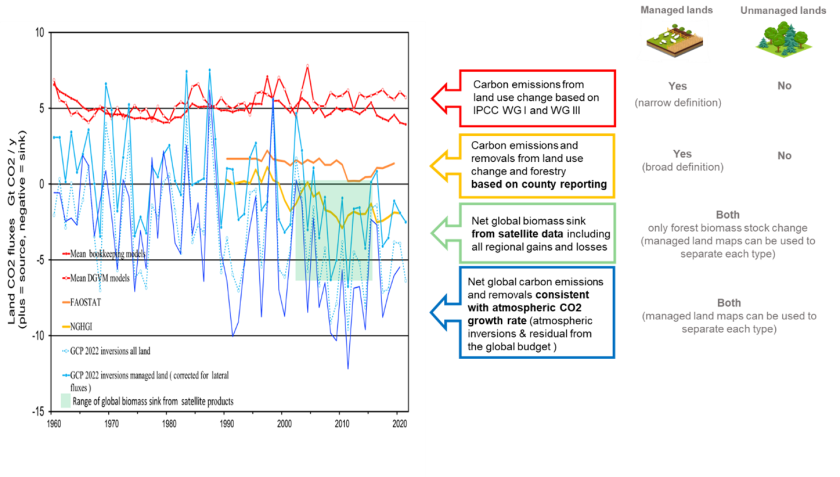

Global forests are crucial in the fight against climate change, but the exact role they play remains uncertain. Estimates of their impact vary widely, with some suggesting they emit approximately 6 billion tonnes of CO2 while others indicate they absorb up to 8 billion tonnes. This uncertainty of 22% in total global greenhouse gas balance makes it impossible to assess if the world is on track staying under 2 degrees climate change and it impedes investments in forest carbon management. This must be resolved, according to Gert-Jan Nabuurs from Wageningen University & Research in a new study published in Nature Communications in Earth and Environment.

Under the Kyoto Protocol, nations agreed to include greenhouse emissions and removals resulting from "direct human-induced effects" in their climate goals. However, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recognized that human-induced effects on land are intertwined with environmental factors such as rising atmospheric CO2 levels (indirect effects). These two categories cannot be separated using current national greenhouse gas inventory methods. As a practical solution, the IPCC Guidelines introduced the concept of "managed land," designating land where countries apply human interventions and practices for production, ecological, or social purposes as a proxy for anthropogenic effects.

Uncertainty on the role of forests in climate change arises, among other things, because only managed forests ( constituting around 55% of global forests) are reported for their CO2 contributions. Unmanaged forests are often viewed as something that countries have no control over and are thus not liable for the emissions occurring from it. Various approaches, including global modeling, National Greenhouse Gas Reporting, remote sensing, and carbon budget balancing from fossil fuel emissions, employ different interpretations of managed and unmanaged. Consequently, estimates range between forests acting as a CO2 source of approximately plus 6 billion tonnes to an net uptake of minus 8 billion tonnes.

This uncertainty complicates the ability to gauge progress toward net-zero emissions as needed to stay under 2 degrees climate change. And it hampers investments in the forest carbon market because in a highly uncertain sector, will not be done. By 2050, the land use sector is expected to remove up to 8 to 14 billion tonnes of additional CO2-equivalent from the atmosphere each year as estimated by the IPCC. To achieve this, accurate estimation is imperative.

In a recent publication in Nature Communications in Earth and Environment, Nabuurs and colleagues from other universities gathered all available estimates for the role of forests in the global climate. The results from various methods as global vegetation models, ground based forest inventories, statistics, and remote sensing and inversions were compiled. A huge variation was found. They argue that it is time for countries and other entities to begin reporting on all forest lands, both managed and unmanaged. The additional information on unmanaged forest would fill a knowledge gap and help tracking progress towards global temperature targets and makes the methods more complete and comparable.

The requisite data and methods for countries to do so, are available. Countries can incorporate the best available estimates of emissions and removals from unmanaged lands in their reporting, drawing on open-access ground-based data, earth observation, and modeling. Initially, estimates of greenhouse gas flux from unmanaged land could be included voluntarily for informational purposes in country reporting. Subsequently, they could factor into official accounting for climate targets. This approach would incentivize the inclusion of carbon-rich unmanaged forests that are vulnerable to climate change and human activities.

Recognizing the current challenges of COP meetings, which tend to yield diminishing results, we propose a more bilateral approach while at the same time the UN negotiations at COPs can work on taking up the full land use sector. Bilaterally, industrialized nations can already provide support and expertise to developing countries in the realm of forest carbon analysis.