category_news

We must learn to live alongside wolves

Wolves have returned to the Netherlands. Over the past few years, the animals have started passing through the Netherlands, with a number of them deciding to settle here. “It’s a unique situation,” says researcher Hugh Jansman. “Wolves have never previously established themselves in a country so densely populated by humans and livestock.” The report published on 6 October sets out all the findings.

For 150 years, wolves were absent from the Netherlands. Over the past six years, 34 individual wolves have been identified and five of them have settled here. That number is expected to grow over the next few years. But according to the second fact-finding study by Wageningen Environmental Research (WENR) The study was commissioned by BIJ12, the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, and the Association of Dutch Provinces.

The authors emphatically argue that “wolves belong here and can easily live in a country like the Netherlands, especially if we’re prepared to give nature the space it needs.” Existing policy now needs to be reviewed, and the study attempts to accurately answer the many questions that have arisen in relation to the review of the government’s Interprovincial Wolf Plan.

The character of wolves

“Wolves are highly intelligent animals, each with their own character. In that sense they are comparable to the dogs we keep as pets: they are individuals. The research has shown us very clearly that wolves are flexible and inquisitive and will readily adapt to the presence of humans,” says Hugh Jansman, an ecologist at WENR.

These qualities mean that wolves could in theory be found anywhere that allows them to safely rest during the day and where there is sufficient food. Wolves see humans as a potential threat and will go out of their way to avoid confrontation. Complications arise when wolves start to associate humans with food, as a result of people feeding them.

Some of them can be curious

“Not all wolves are timid. Some of them can be curious. We’re aware of a case of two young wolves from a nest on a military base in Germany, for example. It’s likely that they were occasionally thrown some food from a military vehicle. These young wolves went on the move, and one was spotted in the Netherlands but was killed in traffic collision when it returned to Germany. Another member of the pack was cautiously approaching cars, and eventually permission was given to cull it. That’s unnatural behaviour, and it's important that wolves remain wild and do not get used to humans,” says co-author and ecologist Joachim Mergeay at the Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO) in Flanders.

“Wolves in the Netherlands and Belgium mainly eat game animals, particularly deer and wild boar. They range over large landscapes, but our natural environment and agricultural lands are becoming increasingly fragmented and parcelled up, leading to increased conflict between humans and wolves. Although the vast majority of livestock injury is currently caused by dogs and foxes rather than wolves, livestock do need to be properly protected from wolves to ensure a sustainable co-existence.”

If a wolf or dog bumps into a electrical wire, it quickly learns to avoid it. “But you have to be consistent when you set that up, otherwise it’s pointless,” according to the researchers.

Compensation

The Netherlands currently has a compensation programme for damage caused by wolves. There are also grants for introducing preventative measures to avoid attacks. Figures show that there has been minimal demand for these resources. “Even in hotspots such as the Veluwe region and in the province of Drenthe, where wolves have caused damage, there have been few applications for grants. I imagine this policy could change in the future,” says Jansman.

“A wolf's territory spans around 200 square kilometres, so if a pack of wolves settles somewhere you will know where measures need to be taken. Not everything can be predicted and controlled, and incidents involving roaming wolves will occur. Nature can’t be controlled.” Jansman emphasises the need for closer co-operation to build support. “The findings of the report can help do that.”

Different populations

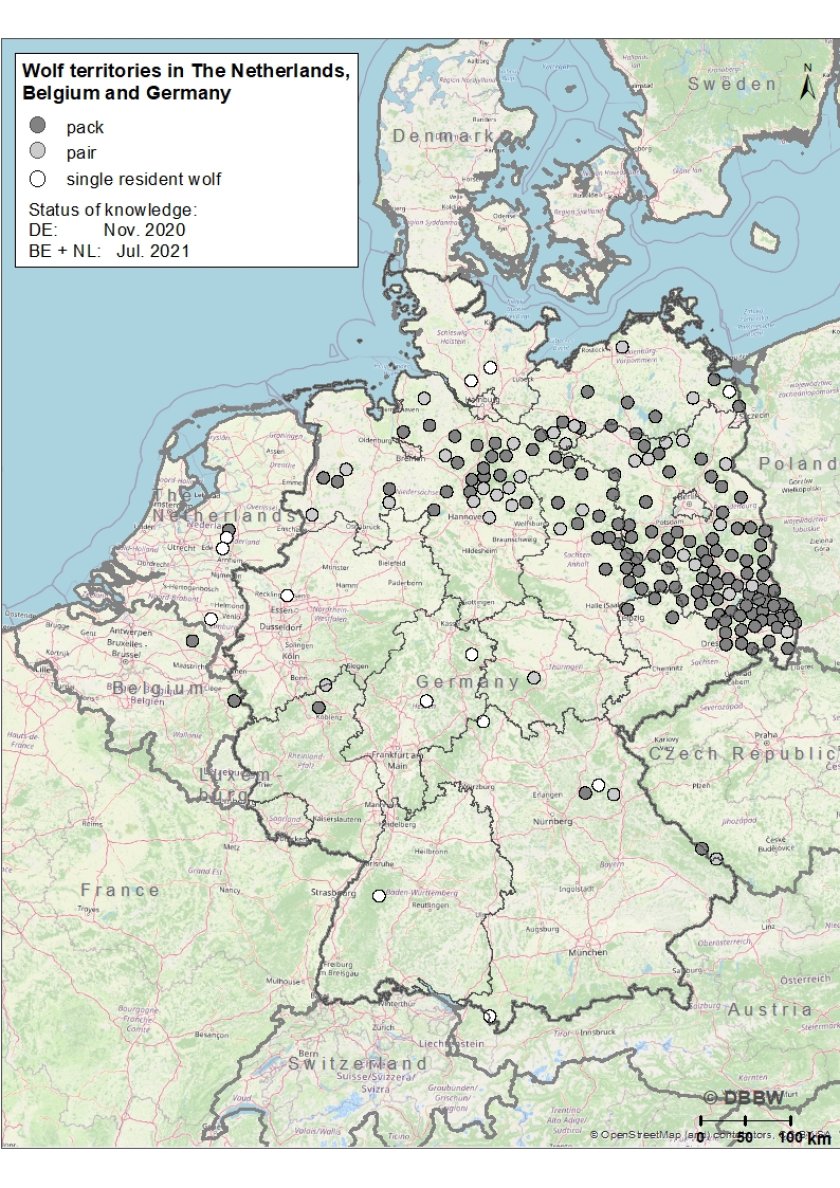

The report presents a clear picture of the growing wolf population in the Netherlands, and of its origins. The researchers found that during 2015-2021, wolves were active on almost half of the surface area of the Netherlands. There are six main hotspots: one in the province of Drenthe, two in Overijssel, two in Gelderland, and one in North Brabant. Four main corridors have been identified. These are areas where movements are concentrated. It’s expected that more wolves will come to the Netherlands over the next few years.

Genetic research has revealed that most of the ‘Dutch’ wolves come from Germany and the vicinity around it. This population is spreading west and south, and the animals are settling in Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, the Czech Republic and Austria. Four of them now live in the Veluwe region. Two wolves have also been identified who came from what’s known as the Alpine wolf population (France, Switzerland, Northern Italy). One of those wolves has now settled in the province of Brabant.

Cooperation with Belgium and Germany

The report that was published on 6 October focused mainly on information gathered in the Netherlands over the past few years, which WENR has a good grasp of. It also looked specifically at data and experiences in other countries, particularly Germany, Belgium and France, as these neighbouring countries are the most relevant to developments in the Netherlands.

While the situation in the Netherlands is different to that of its neighbours, particularly in terms of human populations, the fragmentation of natural environments and livestock density, it’s very useful to learn from experiences in those countries.

The project therefore worked in partnership with the Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO) in Flanders and the Senckenberg Nature Research Society (SGN) in Germany. Both of these research institutes work closely on wolf research in their respective countries and therefore have a wealth of data and expertise. They are also both partners in the Central European Wolf Consortium (CEwolf) which WENR is also part of.

The Interprovincial Wolf Plan is due to be reviewed next year. The findings of this report could help reshape that policy.