category_news

Thousands of wow moments in campus nature

WUR’s campus is home to many different species, as was shown during the Biodiversity Challenge that took place from 23 May until 1 June. The goal of identifying 1000 species was achieved, and WUR came in fourth in the European competition. But how does such a challenge benefit biodiversity? According to Bio Systemics teacher Casper Quist, ‘It is all about wonderment.’

It is just after ten thirty on a rainy Saturday morning. A blue-tailed damselfly is perched on an excursion guide’s warm hand. The group that is under his care is searching for dragonflies and butterflies. As the weather gradually improves, species such as the blue-tailed damselfly creep up out of the vegetation. The excursion guide explains to the group of children and adults that the blue spot on its tail can identify the damselfly on his hand. The group also identifies a green-veined white, an azure damselfly, a silver Y and a cinnabar moth caterpillar.

This excursion is part of the wrap-up of the Biodiversity Challenge. WUR and all of its locations were the scene of this challenge for six weeks. The aim was to encourage as many people as possible to look for species during breaks and lunch. ‘Many students and employees were baffled by the number of living species sharing the campus’, says organiser Mieke de Wit of the Wageningen Biodiversity Initiative (WBI). All citizens of Wageningen and its surroundings were welcome on the final day of the challenge, and, despite a few rain showers, some 250 visitors from all age brackets came to see presentations and join excursions.

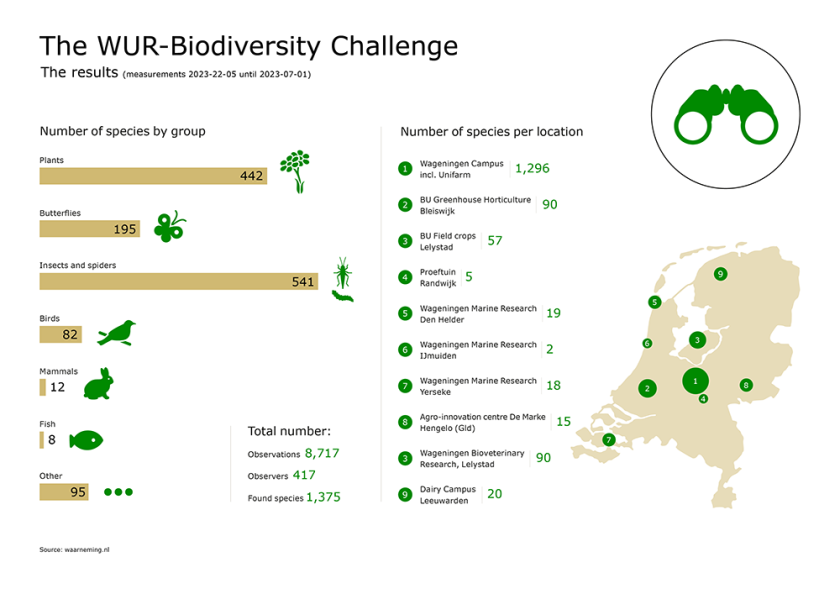

1373 species

Six weeks of searching for plants, animals and fungi at WUR locations resulted in almost 900 sightings of 1373 species. The predetermined goal of one thousand species was easily met. ‘This many different species, even if they are different locations, is quite impressive’, says challenge organiser and Biosystemics teacher Casper Quist. ‘A quarter of all Dutch bird and plant species live here.’ In addition to more common species, a few very rare species were found. This even included a species new to the Netherlands, the Aphis loti.

A quarter of all Dutch bird and plant species live here

WUR was not the only competing university that identified more than one thousand species. Another sixteen universities and university colleges from all over Europe entered the competition, some even more enthusiastically than others. Knowledge institutes from Ukraine, Germany, Belgium and Sweden also achieved the goal, as did WUR. The University of Hohenheim in Stuttgart (Germany) tops the list with a total of 2087 species. The universities shared their achievements during an online event on Friday, 30 June. For example, a single Belgian student identified no less than 680 species and there were an impressive number of sightings in Ukraine.

Experts and guides

There are considerable but explicable differences between the universities. Quist: ‘Some universities have multiple locations and included plots of nature that are not part of the campus. Other universities are located in the middle of a city.’ The number of people that help search for species is also a factor, as is the frequency with which they search and whether they are experts. De Wit: ‘If a beetle expert joins at one university and identifies seventy different species, while only four species are sighted at another university, this does not necessarily mean the second university has a much lower biodiversity.’

People went out at night to find moths

The Biodiversity Challenge may seem like a competition to find the most different species. That, however, is not the main goal. It is all about wonderment. ‘People went out at night to find moths’, De Wit says. ‘And I saw people wading through ponds and streams to get a closer look at frogs, fish and dragonflies.’ Quist took three hundred students outdoors as part of the Biodiversity in the Netherlands course. ‘Most biology students are already interested. The goal is to teach them more about biodiversity. These are the guides that can help ignite the enthusiasm of others, now or in the future.’

First step towards conservation

Rector magnificus Arthur Mol often saw groups of students and employees cruise across the campus armed with magnifying glasses and smartphones aiming to identify species. ‘Doing this with students is extremely important. They are the researchers of the future.’ As a university within the domain of life sciences, WUR values biodiversity. It is not surprising, according to Mol, that we should focus on biodiversity on our own campus. ‘Wonderment is the first step in conserving and increasing biodiversity.’

- Unfortunately, your cookie settings do not allow videos to be displayed. - check your settings

The more species find a home on the campus, the better the area may serve as a linking element between nearby nature reserves. In Wageningen, these are the Veluwe and the Binnenveld. That is why the city of Wageningen was included for the first time this year. Quist: ‘We certainly had visitors on 1 July that would otherwise not have come to the campus.’ They left with more knowledge and wonderment about biodiversity so close to home. ‘Enthusiasm that they may share with others.’

Collaboration within Europe

Quist and De Wit look back upon the one-and-a-half-month Biodiversity Challenge with satisfaction. They hope they have fanned a flame in the students, employees and other interested parties from outside the university. One thing is certain: looking at biodiversity together creates connections. Not just here but also at a European level. The universities are of one mind: ‘Again next year’.

Meanwhile, Quist tries to keep in touch. ‘We want to analyse the data and publish our experiences in a scientific journal. This is the first time universities of life sciences have collaborated at a European level in this way. Who knows what else we may be able to accomplish for biodiversity in Europe.’

Mol also focuses on the future: ‘Wouldn’t it be a great idea to expand next year’s biodiversity Challenge to include more municipalities or, at the very least, all university cities in the Netherlands?’ The organisers stress that the event may spread like wildfire. Although the “wildfire” had better be a rare aphid.